Sofie Vanderlinden

‘The absence of drawing – about the work of Sofie Van der Linden’ by Cornel Bierens 2015

Immediately, at first sight, a surprise is revealed. These drawings evince a wonderful kinship with one of the earliest known street plans in world history: a map of an Egyptian gold mine from 1320 B.C., the oldest surviving papyrus scroll to depict a ground plan. The sketch gives a good impression of the landscape around the gold mine and includes roads, houses, buildings and the mine entrances. No less than 3,335 years and almost the entire human civilazation seperate Sofie Van der Linden from the Egyptian map maker, yet she is obviously somehow related to him. The same intuitive, yet meticulous approach, the same mix of improvisation and conceptualisation, the same gazing from different perspectives simultaneously. Both draw a mining town; both are fully aware that lurking beneath the surface lies an immense depth.

You could say that both the ancient Egyptian and the young artist lean their backs against scientific cartography, like two bookends that keep a row of scholarly books upright. On the left, the Egyptian, on the far side of all this cartographic knowledge and unable to access it, hence forced to sail on sight, on his sense of proportion and the counting of steps. On the right, the artist, who is looking over and above all this accumulated knowledge, who is able to use it freely yet finds something lacking, and therefore prefers to fall back on the method of her prescientific counterpart.

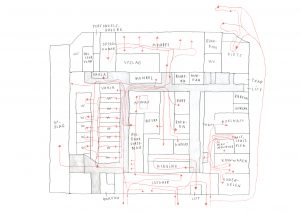

A radical step by Sofie Van der Linden, a form of starting again. Taking note of all the infrastructural and architectural documentation, she wandered through Genk drawing neighbourhoods, streets and buildings in the most rudimentary manner, on the basis of her own movements. And this at a time when official cartography has declared the redundancy of mapmakers and the major atlas publishers have waved goodbye to their last draftsmen. Apparently nothing to be sad about, we have been given fine digital maps instead. Not just geographical and physical maps, but also political, demographic, geological and climatological maps. Road maps have been replaced by patient voices that point us to exits, and thanks to Google Earth, our forefinger on the globe is able to zoom down to street level. We simply seem to have become richer.

But have we really? This is the question Sofie Van der Linden examines in her work, adding percipience through the choice of the stage onto which she has conducted her investigation. The city of Genk is a planological mockery, with a layout that resembles a mythological monster, a lion, a snake and a goat, all at once. The longer one looks at it, the more outlandish it becomes. That the old town was at one time destroyed by the industrial assault that scattered mines across the city grounds, is to some extent, understandable. But that afterwards, when the mines were closed and peace had returned, all the available knowledge and insights were inadequate to turn the city back into an organic whole, defies all understanding.

The drawings of Sofie Van der Linden, however, are intially not made to criticise this sad state of affairs or raise a fist against it – they are no political pamphlet. The artist takes a more subtle approach by accepting the hybrid city, in principle, as it is; she engages with it, putting all the sensitivity into action, and then sees what the outcome of this confrontation might be. The drawings are reports of these adventures. They make clear that even in an alienating environment, there is always an inalienable human core that remains intact, and that the nooks, crannies, rocks and concrete blocks are never too far to have new life breathed into them.

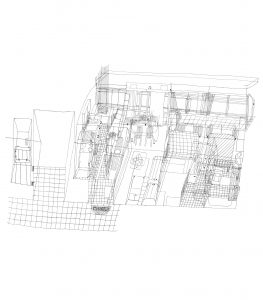

The secret waepon is attention, which is perhaps the main subject of this work. Attention described as standing still in the midst of everything that moves. This is an art which the artist has – entirely in her own way – thoroughly mastered. The roads, roundabouts and parking lots she draws, all of them emblems of mobility par excellence, are entirely silent and empty, there is not even a dog roaming about. Nevertheless, they bristle with activity, if only because of the hundreds of arrows on the road, which seems to create a traffic jam all of their own. One looks at it as if it were a comic strip, frame by frame, arrow by arrow, and yet together they create an undeniable celerity.

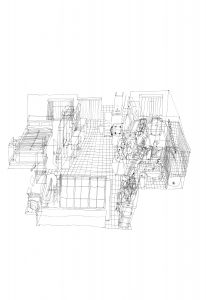

This busyness is evident elsewhere as well, even if there are no traces of humans, animals or plants and everything looks entirely deserted. The megalomaniac City Hall of Genk is depicted as if it had been entirely wiped out by a bomb – everything but the rebar which has somehow remained standing, untouched. All those lines are sketched with the repetitive accurancy typical of rebar workers. Their work, at times of great beauty, is always but briefly visible; fortunately, Sofie Van der Linden allows us to contemplate it much longer. Hers is an intuitive geometry; all the lines are connecting lines, neural pathways. With her eloborate detailling, she manages to give the building a soul, or better, the elaborate detailling itself is the soul. Every pencil line has been drawn with the utmost care, and this undoubtedly also applies to every step the artist took when she was walking around to take in the building.

It is therefore not suprising that she situates herself in the tradition of artists who created a whole body of work on the basis of their walking motions, such as the Dutchman Stanley Brouwn (b.1935). His work is limited to two subjects, distance and movement, which he investigates using three measures, the ‘sb-foot’, the ‘sb-ell’ and the ‘sb-step’. As a pure conceptualist, he adheres to the belief that an artistic idea is already complete in its linguistic form, and therefore requires no physical realisation. Ironically, his most famous project, This Way Brouwn‘ does have a physical form. Random pedestrains drew how he could reach a certain spot in the city, and the collected sketches, stamped with ‘this way brouws’, constituted the exhibition.

Sofie Van der Linden is not a pure conceptualist; her ideas are infeasible outside of the drawings in which they are conceived, just like those of the Egyptian map maker. Yet she also somehow shares kinship with the Dutch pedometer, albeit through a different branch. She shares Stanley Brouwn’s hyper-consciousness, punctuality, immaculacy, control. One can tell from her drawings that she is a strict director who constantly instructs her pencil: ‘This way Van der Linden!’

What all three family members have in common is the step as the measure of all things, the registration of the world through the motion of the legs, a thinking as a rolling of the foot. It is wonderful that this never ends, that there still are artists emerging who limit themselves to that which can be walked on. While we have budget airlines shoot us to the other side of the world en masse in the hope of once seeing something worthwhile, these artists stay at home and use their graphite to dig up jewels from the asphalt. There undoubtedly is a connection between the two phenomena. We might wonder why, if we never really manage to see anything special at home, we might start looking more attentively in far-away exotic places.

There are writers who have asked themselves this question, and who have written a book called Journey through my room. The French author Xavier de Maistre (1763-1852) and the Dutchman Maarten Biesheuvel (b.939), for example. It is clear to us that they share kinship with Sofie Van der Linden as well. Like these writers who roam around their rooms, decribing them, she perambulates through residential neighbourhoods and buildings, over roundabouts and parking lots, and draws them. The action radius is limited, the sense of depth required.

This takes courage, as Maarten Biesheuvel realises all too well ‘When I contemplate things her in my own room,’ he writes, ‘I could go insane with fear because of the eeriness of existence much more easily than any arbitrary accountant from Alkmaar who travels to Africa to stand on Table Mountain. The only thing he might think is: Nice view, actually, and the weather is good, fortunately, a warm meal in about an hour…’

For Xavier de Maistre, things are different. He is forced to travel throughout his room because of six weeks of house arrest after a prohibited duel. Were it not for the reason, he would, as a man of the world, never have entered into this confrontation with himself. But as this is how things stand, he can see the value of it, in fact, he is intimately grateful to his judges. ‘They have forbidden me to traverse a particular city, a particular place, but they have left me the whole universe: infinity and eternity lie open to me.’

Sofie Van der Linden is no stranger to both writers’ experience. She knows that for those who wander through Genk, the views are often not pretty at all, the weather awful and the food not hot enough. But she also knows that everything can radiate infinitely as soon as one pauses for a moment and starts drawing with all one’s attention.